What Comedians Teach Us About Storytelling

I’ve always admired stand-up comics for their quick wit and confidence, but I never thought I had much to learn from them because I don’t consider myself a comedic writer. In fact, in my experience, the harder I’ve tried to make people laugh, the harder I’ve failed.

Then, as I was watching Taylor Tomlinson’s new comedy show on Netflix, I realized how stupid my assumption was. After all, some of the best stories I’ve ever heard have been told by comedians. I mean, if you say Dave Chappelle, I immediately think of his story “3 a.m. in the Ghetto” or picture him dressed up like Prince, proclaiming, “Game: Blouses.”

Those routines aren’t just funny. They have rhythm and repetition. They contain surprise and truth. So lately, at the end of a long day when I’m too tired to write, I’ve started to watch stand-up and analyze what the comics are doing. Not so I can get laughs (see above), but so I can re-create the incredibly entertaining ride they take the audience on.

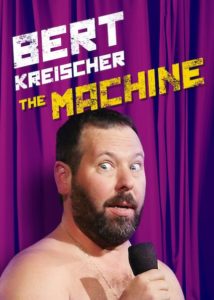

Yes, it’s a kind of geeky thing to do. But trust me, it’s a fun, fast way to internalize the same rules we try to master in written form. Don’t believe me? Watch “The Machine” routine by comic Bert Kreischer (below). It’s a lewd and crude (you’ve been warned!), but also a perfect example of how to tell a compelling story. In a second, I’m going to break down why it’s so effective, but first, watch it if you haven’t seen it before.

Crazy, right? So how did he do it? Simple: By applying the same narrative structure and tools all those “how to write” articles and podcasts recommend. You probably didn’t notice it because you were too busy laughing. Nevertheless, on closer inspection, his story:

1) Starts with a simple, compelling hook: “When I was 22, I got involved with the Russian Mafia. Here’s how it happened.” Bert promises to take us on a crazy ride. The potential for conflict is high. Then he …

2) Establishes the story’s main character: himself. He paints himself as a stupid college student that everyone can relate—or perhaps feel superior—to. His desire is implied: to skate through university as long as possible, maximizing the partying and minimizing the work involved. Then his teacher …

3) Presents the protagonist with a choice: Leave the very difficult Russian class he didn’t mean to sign up for or stay and get a C no matter what. He agrees and the story begins. With each step that follows, he …

4) Builds tension as he takes more and more Russian classes and falls further and further behind everyone else. Stakes increase as he agrees to go on a class trip to Russia even though he can’t speak a word, then learns that the trip will be supervised by the mob. Above all, his actions become more unexpected, and the consequences logically lead to even more problems. First, he talks to the forbidden mobsters, then he befriends them, then shenanigans ensure until his new besties ask him to join them in robbing a train. Say whhaaaaat? This whole section of his story was so instructive to me because sometimes I get so caught up in making a story seem “realistic” that I end up landing on “boring” instead. Nothing about this story sounds believable on its own, but in the context of his character and the specific setting, I bought the whole thing. And I was so busy wondering what would happen next, I didn’t have time to nit-pick. Then, out of nowhere he …

5) Pauses the narrative for backstory about how he would never cheat on his wife. At first, this seems a weird tangent. Often, stopping for backstory is a mistake, but in this case, it accomplishes three important things. First, it clarifies character, because at this point, the audience could be forgiven for thinking this guy is a jerk. It also explains his far-fetched choice, which helps a potentially disbelieving audience stay engaged. Finally, and most important, it stretches out the moment of greatest tension and suspense as the audience wonders whether he will really rob the train and what will happen if he does. Finally …

6) The consequences of his choice play out. Bert robs the train, then simultaneously learns the error of his ways yet also escapes punishment, which feels appropriate for a comedy. Short story writers and novelists often advise ending your story where it began or echoing a refrain from the lead, and Bert chooses a variation on this technique by reusing a punchline from midpoint in the story: “F*^@ that B#%@, this is Russia!” The repetition not only feels surprising yet inevitable, it crystalizes the theme of the story.

Who are some of your favorite stand-up comedians? Go watch them and analyze them yourself. If nothing else, you’ll end up smiling.