The ‘Empathy Machine’ of the Novel & Human Brain — Author Richard Powers

I have this strange thing I do when I’m faced with a task that is sad or scary, or circumstances that just plain suck: I pretend I’m one of my own kids.

I think of what advice I’d give them, and then I follow it. In this frame of mind, I’m a better person–calmer, smarter, more forgiving, less self-pitying.

So when I heard the summary for Richard Powers’ new novel, Bewilderment, on NPR one morning, I wondered if Powers was performing the same trick. The story is about an astrobiologist father struggling to help his troubled, deeply empathetic 9-year-old son come to terms with the extinction of so much life on Earth at the hands of people. Knowing that Powers’ latest book follows his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Overstory, which centered around the destruction of rainforests, I speculated: Was he projecting his own grief into this new boy, Robin? Was he trying to find strength, to be his best self in the character of the grieving single father, astrobiologist Theo Byrne?

As it turns out, yes—in more ways than one.

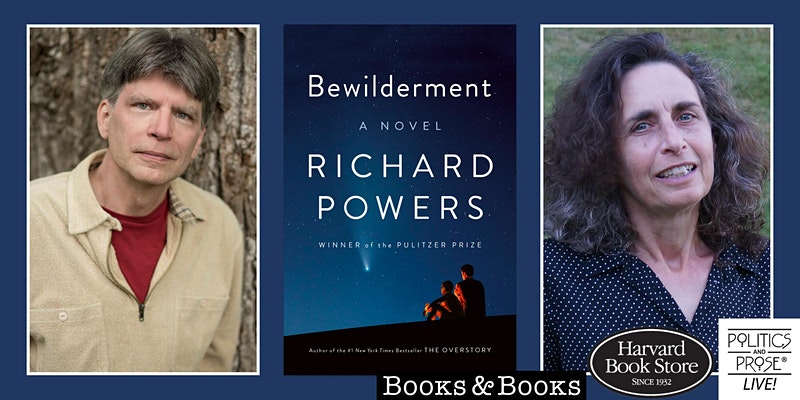

Powers spoke about his new novel Tuesday, the day of its release following its nomination for a National Book Award, at an online event I attended sponsored by Books & Books in Coral Gables. Powers read a passage of his novel, which described the character of Robin through the eyes of his father. It gave me chills:

His second pediatrician was keen to put Robin “on the spectrum.” I wanted to tell the man that everyone alive on this fluke little planet is on the spectrum. That’s what a spectrum is. I wanted to tell that man that life itself is a spectrum disorder, where each of us vibrated at some unique frequency in the continuous rainbow. Then I wanted to punch him. I suppose there’s a name for that, too.

Powers said he combined the “sweetness and bitterness” of several children who are dear to him with his own idiosyncrasies to create Robin’s character.

“I was remembering my own strangeness. And I was actually the father, taking care of my own strangeness,” Powers said. “The book turns on this question of how to give this boy solace … about this question regarding having empathy yet surviving a culture that is the antithesis of this.”

At the start of the novel, young Robin (who is grieving his mother’s death) has trouble controlling his anger and is nearly expelled from school. His father resists doctors’ advice to medicate him and, instead, the two head into the Great Smoky Mountains for a camping trip. The father and son star gaze and imagine far-flung planets. Later, Theo becomes desperate enough that he allows his son to take part in experimental neurofeedback therapy.

It works–at first.

While writing the novel, Powers said he purposedly grappled with an issue many environmental writers struggle with when reporting on climate change – how many depressing facts, how much doom and gloom, to include?

“Is it possible to create a story, to ask a reader to watch a child go through hell and not turn away?” he asked. “It’s a delicate balance, between the light and the dark in a story.”

He added that fiction is uniquely suited to put people in others’ shoes and open their minds to new possibilities—much like the technology in his novel, which allows Robin to experience some of his mother’s positive brain patterns recorded before her death.

“It is to be inside a kind of empathy machine. Simply asking a person to play or pretend a perspective other than theirs … makes this empathy leap that we’re going to need if we’re going to survive.”

The technology is far beyond current capabilities, which means the novel could be classified as science fiction. Yet the event moderator, Pulitzer-Prize winning writer of The Sixth Extinction Elizabeth Kolbert, said she didn’t think of Powers’ literary style as scifi. Powers pushed back a bit:

“My own relationship to sci fi is a long and winding road. When I was Robin’s age, I adored it. When I started getting serious about literature as a life pursuit, I made a mistake, which was to say, ‘I’m going to put away those childish things and focus on the real.’ We were blind to the fact that the [sci fi] books were doing something hugely different and hugely important. Having come back to sci fi … I regret the time away. And I also see and readily cheer that the entire field has been … folded back into literary pursuit.”

Powers also addressed the question of why he focused much of the book on astrobiology if he is so concerned about Earth’s environment. (“Why worry about other planets when so much life, we’re obliterating here?” Kolbert asked.)

“To point our eyes outward is not to turn our eyes away from the Earth,” Powers replied. “Astrobiology is ‘What is life? How rare is it? How did it get started?’ They are almost religious questions. In fact, why say ‘almost’? It’s the same question the Bronze Age people were asking when they looked to the sky. And the answers affect how we look at ourselves.

“What would that do to our sense of stewardship, [if we knew] that [life] only happened once and here we are? It raises the stakes. And if life is everywhere? It would break us of this habit of human exceptionalism. It would be humbling and force us to think differently about ourselves.”