Re-Imagining the Afrofuture

How do you find hope amid hardship? Start anew when you’re just plain exhausted? Or even imagine a bright future when reality seems so bleak?

At this particular moment in history, as we start a new year following the catastrophe that was 2020, I am struck by the importance of a particular brand of science fiction and fantasy that speaks directly to these questions:

Afrofuturism.

Most people know of this sub-genre from movies like Black Panther, but Afrofuturism is so much more. It can be smart and subversive and inspiring in all the best ways and is found not only in movies and novels, but also music and art.

Ian MacDonald, assistant professor of science fiction at Florida Atlantic University, teaches an entire course on Afrofuturism not far from my home. (Side note — No fair! Where was that course when I was in college?)

The following is an edited, condensed version of our conversation about Afro-futurism and how it is particularly relevant now. (Scroll to the bottom of the talk to see his recommended reading.)

So, Professor MacDonald, how would you define Afrofuturism and its cousin, Africanfuturism?

In many ways, the meaning is in flux. It’s about technology and the future and blackness.

It’s about the ability to conceive of the present as something else – that oppression can be transcended or broken through. It’s where the intersection of the mythic and the scientific opens up landscapes that are spectacular. (Chuckles) I started out knowing what it was, and now I’m not sure what it is.

Note: Check out author Nnedi Okorafor’s blog post to read how she distinguishes Afro- from African-futurism.

Why are Afrofuturism and Africanfuturism important?

It’s the most exciting kind of scifi, to me. Because of the world we are living in right now, politically, the role of black voices is so important. This literature has always been a literature of protest, of responding to structural deficiencies on the level of race, class and gender. It drags those contexts into further relief with what’s going on around us. This is sort of a dystopic moment … and [Afrofuturism] opens up spaces for utopian thinking.

Why did you think so many black writers are choosing to write science fiction and fantasy?

People talk about the black experience as being intrinsically tied to science fiction. [Writer and musician] Greg Tate has said, ‘Aliens on a giant ship kidnap you, take you to an unfamiliar planet and genetically manipulate you. That’s not scifi, that’s my history.’

And now, we know about a lot of these things [regarding race-related police brutality] because of technology. Big Brother, who was watching us, is now being watched back. The camera has opened up a truth unknown.

But Afrofuturism isn’t actually new. It’s been growing since the 1950s, even earlier. Why has it taken so long to be recognized?

The speculative imagination has always been there, it just didn’t fit what the international publishers thought was ‘African literature.’ They wanted post-colonial … stories meant as a virtual tour guide for white readers.”

There was also the idea that somehow this [genre] was for children. Now it’s a moment where science fiction is finally getting it’s due, and I think it’s because of African writers, particularly black women writers.

What is it like for you to teach Afrofuturism at this moment in history? How do you students respond to it?

They love it. Half of my students are of color. They’re enormously interested. [Undergraduate students] may have seen it in movies and comics, but maybe they have not seen the texts. First and foremost, I want them to read works by black writers. I want them to know these works are out there.

[With my graduate students], the conversation is all about humanism. What is it to be human if, in science fiction, it’s always been about the construction of the ‘white future,’ where you’ve managed to create a world where you don’t have to think about race? That’s where Afro-futurism steps in. It says, ‘There will be black bodies in space.’

So Afrofuturism not only questions harmful institutions and stereotypes made by society at large, but also of those found in science fiction itself. Can you give me some examples?

This is science fiction that questions science fiction. [It questions the idea] that science will make us the best humans we can be … the continuation of the narrative of exploration, the same language used in colonial literature to de-humanize people ‘for progress.’

[It questions] the distain for nature … the idea that to succeed you have to cut out anything tied to the past, that to hold onto that is nostalgic or ‘primitive.’ It’s taking these codes and flipping them and then holding the genre responsible for its role in them.

If people are new to Afrofuturism, can you give them a list of accessible novels to start with?

For a historical perspective, there’s Black No More by George Schuyler (1931) and Mumbo Jumbo by Ishmael Reed (1972).

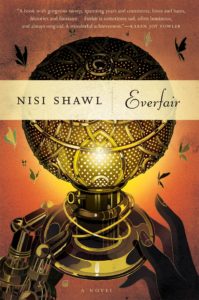

More recently, there’s Midnight Robber by Nalo Hopkinson, Everfair by Nisi Shawl, After the Flare by Deji Bryce Olukotun, and War and Mir by Minister Faust.

And for those wanting a more extensive list, MacDonald provides the following (broken up into three categories):

- For Short Fiction:

Dark Matter and Dark Matter: Reading the Bones edited by Sheree Thomas

Octavia’s Brood ed. by Adrienne Brown and Walida Imarisha

Steamfunk, ed. by Milton Davis and Balogun Ojetade

AfroSF, ed. by Ivor Hartmann

Mothership, ed. by Bill Campbell and Edward Hall

So Long Been Dreaming, ed. by Nalo Hopkinson and Uppinder Mehan

2. For Novels on SciFi side of Afrofuturism:

Blake, or the Huts of America (U.S.), Martin Delany (1859)

“The Comet,” (U.S.), W.E.B. DuBois (1920)

Black No More (U.S.), George Schuyler (1931)

Mumbo Jumbo (U.S.), Ishmael Reed (1972)

Trouble on Triton (U.S.), Samuel Delany (1976)

Dawn and Parable of the Sower (U.S.), Octavia Butler (1987, 1993)

Major Gentl and the Achimota War and Big Bishop Roko and the Altar Gangsters (Ghana), Kojo Laing (1994, 2006)

Astonishing the Gods (Nigeria), Ben Okri (1995)

Midnight Robber (Jamaica-Canada), Nalo Hopkinson (2000)

Wizard of the Crow (Kenya), Ngugi wa Thiong’o (2006)

Mindscape (U.S.), Andrea Hairston (2006)

Best of All Possible Worlds (Barbados), Karen Lord (2013)

Binti, trilogy, Lagoon, and Who Fears Death (U.S.-Nigeria), Nnedi Okorafor (2015, 2014, 2010) [Note: Okorafor says the term Afrofuturism can be too reductive and does not apply to her work. She prefers Africanfuturism or Africanjujuism.]

Everfair (U.S.), Nisi Shawl (2016)

Nigerians in Space and After the Flare (U.S.-Nigeria), Deji Bryce Olukotun (2014, 2017)

The Coyote Kings of the Space Age Bachelor Pad and War and Mir (U.S.), Minister Faust (2004, 2012)

Futureland (U.S.), Walter Mosley (2001)

Lion’s Blood (U.S.), Steven Barnes (2002)

A Killing in the Sun (Uganda), Dilman Dila (2014)

3. For Novels on the Speculative Fantasy side of Afro-futurism:

Thomas Mofolo, Chaka

DO Fagunwa, The Forest of 1000 Daemons

Amos Tutuola, The Palm Wine Drinkard

Ben Okri, Starbook

Samuel Delany, Tales of Neveryon

Octavia Butler, Wild Seed

Nnedi Okorafor, Akata Witch

NK Jemisin, The Fifth Season

Tomi Adeyemi, Children of Blood and Bone

Kai Ashante Wilson, Sorcerer of the Wildeeps

P Djeli Clarke, The Black God’s Drums

Victor LaValle, The Ballad of Black Tom

Marlon James, Black Leopard, Red Wolf

Tananarive Due, My Soul to Keep